Digital Signatures of the Baroque

by Alex Went, on Feb 6, 2018 2:56:23 PM

Encoded dates started to appear on vernacular architecture between the Rhine and the Danube from the late 1500s onwards. But the real craze appears to have been concentrated in Bohemia, originating in the mid-seventeenth century and reaching its peak in the early-to-mid-eighteenth. Known as 'chronograms' from the Greek for 'time writing' – they flourished in eighteenth-century Europe, particularly on memorials and medals, but also in books and manuscripts.

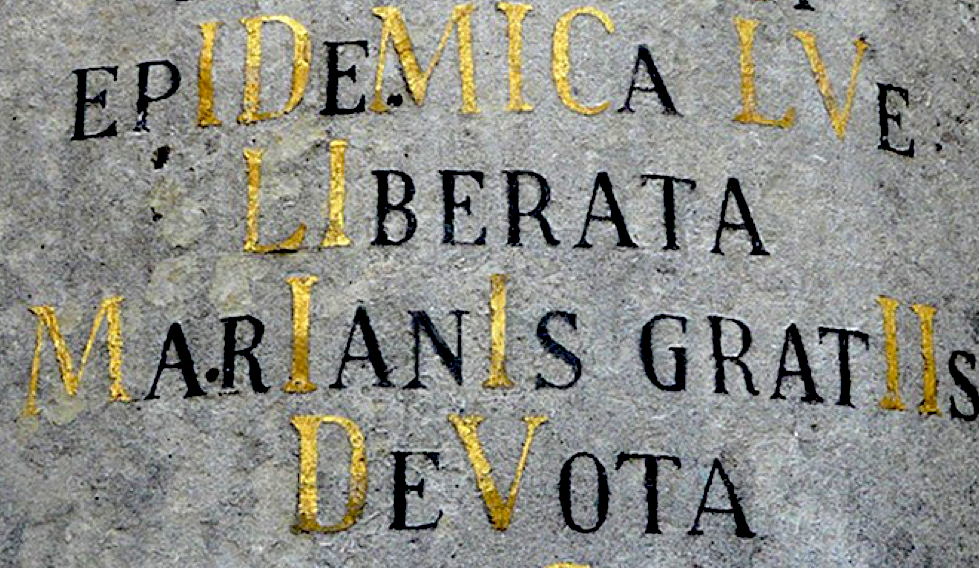

The accepted system of chronogrammatic encoding depends on an understanding that all letters that can be read as Roman numerals will be included in the final count; it is not considered good practice to be selective. Certain letters are picked out in capitals, highlighting their dual function as letters and numerals, and giving the entire inscription the air of a riddle. And indeed, when added together, these letters give the year of composition or construction.

In this essay I propose a number of reasons for the phenomenon.

Firstly, an emphasis on dedicatory inscriptions – particularly in Latin – coincided with the wave of baroque architecture which dominated Europe during the seventeenth century. In Bohemia, the baroque style was strongly identified with the resurgence of Catholicism after the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), as evidenced, for example, in the statues erected on Prague's Charles Bridge in the second decade of the eighteenth century. The idea, common in classical and biblical texts, was that 'the stones will speak' ('saxa loquuntur'), with inscriptions below the statues transmitting the truths of their time to future generations.

Secondly, Bohemia lay on a fault line between the Holy Roman Empire and that brand of protestantism which had originated in the sermons of reformers including Jan Hus and, later, Martin Luther. Although chronograms were employed by Catholics and Protestants alike, it is tempting to associate their rise with the Europe-wide trend for coding and encryption which grew up as a result of the need to conceal or equivocate in matters of religious faith.

Thirdly, chronogrammatic inscriptions, with their appeal to classical learning and patterning, would have been seen as a representation of the power of God, particularly in those inscriptions where the Roman numerals are both enlarged and picked out in gold. More importantly these academic puzzles would have expressed the power of the Church itself by emphasising the intellectual distance between a book-learned clergy and an ignorant laity. For Anna Kapuścińska and Piotr Urbański, co-authors of a paper on the Lutheran poet Paul Zacaharias, chrono- grams "seem to work as intellectual stimuli intended to engage the reader in a sort of divine game, which invigor- ates the mind and aims to inspire righteous thoughts, leading to the spiritual improvement and moral purity".